Music

Baby I’m A Star: Purple Rain, Reexamined

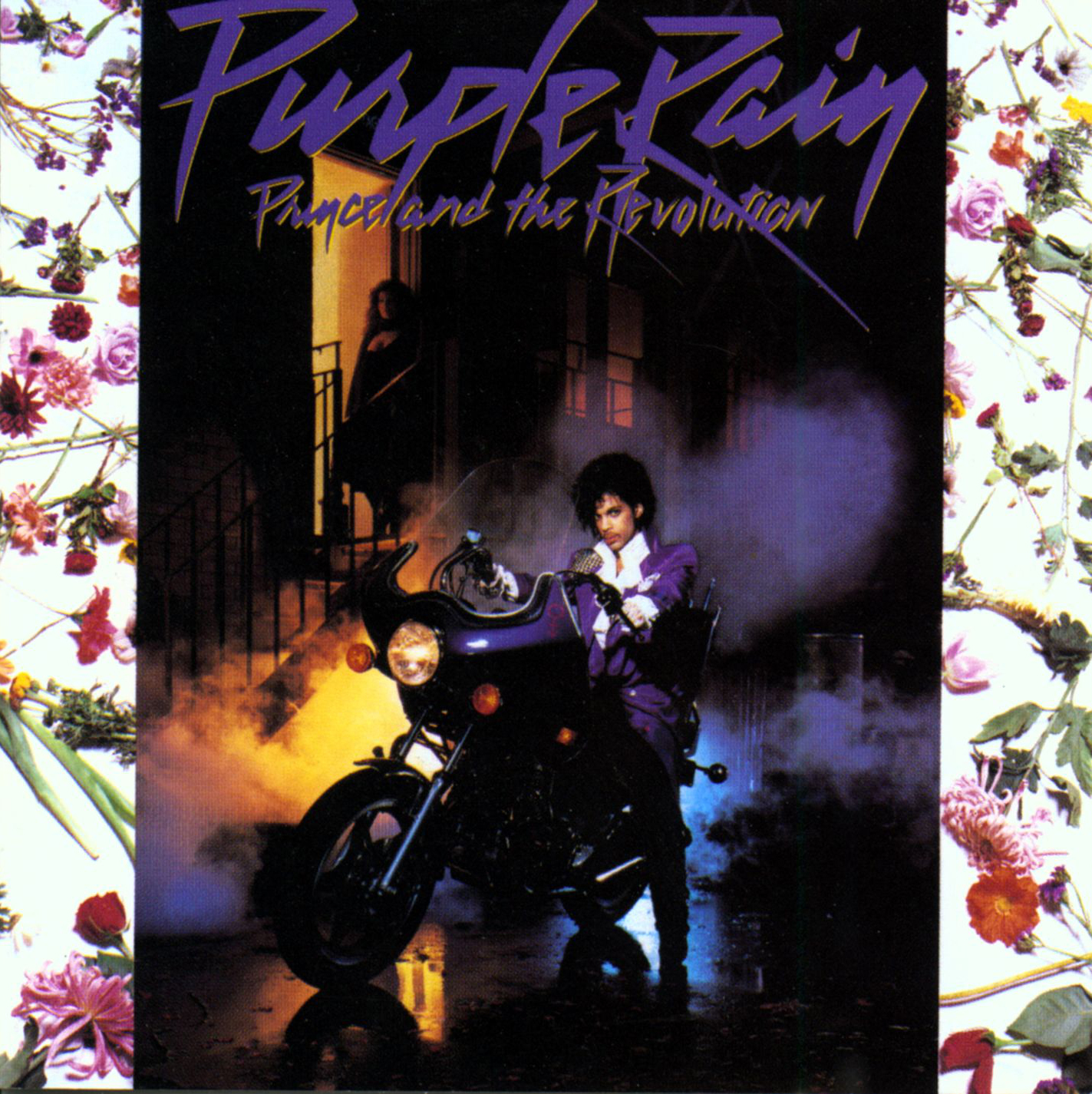

In late April of 2016, the masses returned to an album from 1984. It featured an iconic photo on its cover: a man in a purple crushed velvet suit, astride a purple motorcycle; behind him, silhouetted in a doorway lit by orange glow, an enchantress in black.

They hit play and heard a wavering church organ, as Prince Rogers Nelson intoned the opening sermon:

Dearly beloved

We are gathered here today

To get through this thing called Life

Electric word, Life

It means forever and that's a mighty long time

But I'm here to tell you

There's something else

The afterworld

A world of never ending happiness

You can always see the sun, day or night…

With Prince’s abrupt passing, these words inevitably took on new meaning for the masses; the eulogy became an elegy. You saw it all over social media. You heard it in Prince tributes at parties and dance clubs. Because this is what we do when we lose a beloved artist: We listen and re-listen to their finest moments. The simple act of listening pays the truest homage to the artist.

And as far as the masses are concerned, Purple Rain was Prince’s finest moment. Its accessibility remains undeniable: Five hit singles on a nine-track album. A searing mixture of funk, new wave, rock and R&B balladry; white and black musical worlds reunited. It made Prince the first singer to achieve a simultaneous number one album, single, and film.

But beyond it populist appeal, at its heart, Purple Rain is simply a joyful album. It’s comforting even during its psychedelic moments. It’s beautifully abloom—a faithful snapshot of the Purple One’s artistic élan, effusive delight, and indelible style; his fluid pivoting between the spiritual and the sexual, and above it all, an unwavering commitment to virally infectious, freaky, funky dance music. Who could listen and re-listen to Purple Rain’s 44 minutes of pure uplift, and still feel sad at the end?

“Let’s Go Crazy,” “Computer Blue,” and “Baby I’m A Star” take your hand and lead you straight to the dancefloor. Between those beacons lie gorgeous chamber pop (“Take Me With U”), sweet balladry transmuting to gritty soul (“The Beautiful Ones”) and the glorious raunch of “Darling Nikki,” which effectively birthed the Parental Advisory sticker.

Next up, “When Doves Cry”—a circuitously hooky curiosity that became the year's biggest hit. It models the drum machine & synth-driven “Minneapolis sound” that Prince had sculpted to perfection on 1999. The man could pull the funkiest, most organic-sounding grooves from sterile electronic boxes.

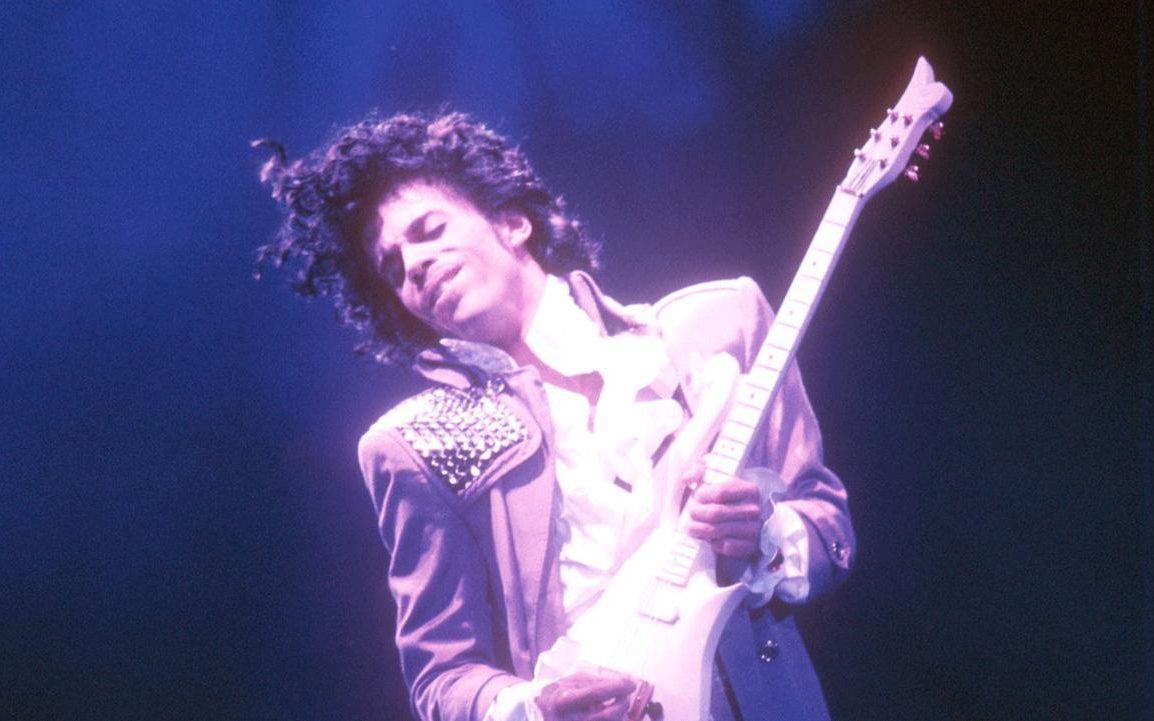

The musicianship throughout Purple Rain is, still, stunning. The addition of Prince’s new band, The Revolution, to the album credits was no small gesture. It was Prince recognizing, for the first time, his musical collaborators: The renaissance man had brought some worthy company into the studio, and they were driving him to new heights.

Prince was a black man who played guitar like he was from another planet, so the lazy critical comparisons to Jimi Hendrix were inevitable. Prince rightfully rejected them, but he nonetheless shared a certain signifier with Jimi: an instrumental virtuosity that spotlighted the song itself, rather than overshadowing it. Witness the “Flight of the Bumblebee”-style guitar flurries in “Computer Blue,” or the fiery opening lick to “When Doves Cry.” These brief but blinding exhibitions set Prince apart from a multiplicity of “guitar heroes” who thoughtlessly noodled away on three-minute solos. Paradoxically, Prince was too busy being a pop star for such self-indulgence. And on the rare album moments where he does stretch out on guitar, the searching beauty of his solos (“The Beautiful Ones”, “Purple Rain”) recalls Carlos Santana’s mystic approach—the guitar solo as spiritual worship.

And Purple Rain is a highly spiritual album. Long before he converted to a Jehovah’s Witness, Prince was either invoking or embodying a higher power in his lyrics. This was no doubt somewhat rooted in his religious upbringing in the Seventh-day Adventist Church, which focused heavily on the ever-nearing apocalypse. “He's comin'/He's comin,” Prince repeats on “Let’s Get Crazy.” “I'm your messiah and you're the reason why” comes the confession on “I Would Die 4 U.” The title track itself is a straight-ahead gospel tune. Even “Darling Nikki” contains a tongue-in-cheek, backward-masked testimony: "Hello, how are you? Fine fine 'cause I know that the Lord is coming soon.”

Of course, many pop artists invoke the divine. Doing so aligns them with archetypes and grants them the air—if not the authority—of the supernatural. But few artists married that authority to such singular musical ambition. The displays on Purple Rain have seen few equals in the last 32 years. That’s why the musical luminaries of today paid Prince homage, right along with the masses.

You’ll hear pieces of Prince in the sweetly salacious delivery of The Weeknd, or the falsetto-funk vocalizations of Pharrell and Miguel. You might see him in the consummate musicianship of D’Angelo or Questlove. You glimpse reflections of his fearless, visionary style in Janelle Monáe, Lady Gaga, and Andre 3000. You witness him in the true originals and innovators, and you hear him in the pop chart wonders. On Purple Rain, Prince ruled those worlds equally.